Review

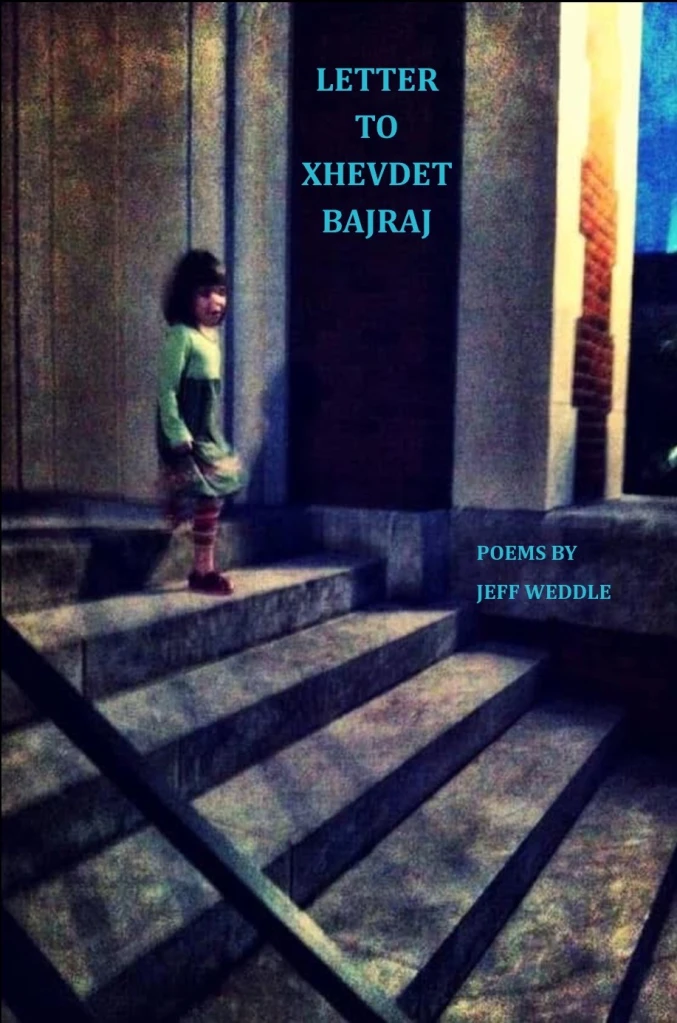

Ask the Sunlight on a Sleeping Dog: Letter to Xhevdet Bajraj by Jeff Weddle

Review by Peter Mladinic

UnCollected Press

ISBN: 9798990558588

Jeff Weddle is a poet who reads other poets. Jeff Weddle is a philosopher whose ideas come not out of books but out of lived lives, of friends of now and then, of family, and of people met along the way. A traveler, a seeker, a son, a husband, and a father, he speaks of the past and for the present. His new book, Letter to Xhevdet Bajraj, is about people with whom he has spent time. His particular experiences—bar hopping with friends, watching the sun rise in Key West, imagining a writer from the 1940s walking in a park—mirror the human condition. Familial and fraternal love, sexual love, and love of life are Jeff Weddle’s topics. To quote Ron Whitehead, U.S. National Lifetime Beat Poet Laureate, “His poems are the real deal.”

Poems about love of life suggest people are impacted by fate, and, if fortunate enough, people live by their choices. Caring for others is the key, not to a personal relationship with a higher power, but to a personal relationship with the self. “That’s the Way It Was,” with its chant-like repetitions, exacting images, and poignant narrative elements, opens the book.

Listen to the music in the voice of one who’s been to the edge.

Drunk in San Francisco, drunk in Key West,

drunk in Daytona, in St. Augustine,

New Orleans, Denver, New York, Boston,

Columbus, Concord, Memphis, St. Louis,

Kansas City, Nashville, Louisville, Lexington.

All over Maine. Here and there in Canada.

Good bars, bad bars, bars where despair

is standard, bars that could get you killed

and sad strip clubs.

Coming to in a hedge. The worst knife

to the heart. Curtis talking to me

like I was sober and awake

so the cops wouldn’t arrest me

in that greasy spoon in West Virginia.

Drunk on sidewalks I don’t remember.

Weddle’s rhythm builds and builds until his reader is right there in the fluorescent light of that greasy spoon, a witness to a small act of compassion that alters the course of things. While there is sadness in this passage, there’s no regret. At the end of the poem, the reader comes to “I’m …as good as I’m able to be,” which speaks for all. Love of life is a matter of longing, and private celebration, “the quality of light / that lodges in the chest / and makes breathing / almost holy.” To love life is to live in the bittersweet, real world. “Accept It” begins, “You will always be the monster / to the fly” and concludes, “The fly hates you, though you / are full of love. The world / is just like that, unfair.”

Sexual love. In “A Chance Encounter,” the poet talks about “a city / everyone knows by heart / but can never find?” The question mark leaves the line open-ended, a reference to the unfinished lives of the two people in the poem. Sexual love expresses desire. “Ménage à Trois” includes a boy and a girl he is with, and the girl he wants to be with. “Lost Motel Rendezvous” is about love and death. A young couple is in a room that had been occupied by a person who is now deceased, and whose corpse, unbeknownst to them, is still there. “This also did not stop them. / Naked, in their ecstasy, they breathed it in, gulped the tainted air.” “In Memory of a Woman I Never Knew” is speculative. “The night, you will recall, was littered / with stifled need and pale desire.” “All You Need is Love” tells a story of desire: “the girl who worked in the flower shop / hungered for the touch / of the Croatian boy / who delivered her milk.” In “I Loved Lucy,” love is romantic. The speaker gives a girl flowers in a pop bottle he’d “collected / by the side of the road.” In “Lovers in Love,” love is desperate, “the sort of love / that destroys sleep / but feeds dreams.” And in “At the Winn Dixie,” love is ephemeral. “The pretty cashier” has two customers: one wears a “Read Banned Books” t-shirt, the other leaves disgruntled.

We watched him stalk out

and then she said to me,

“It’s probably because I said

I liked your shirt.”

I agreed and she smiled a lovely smile.

The other guy was old

and I’m sure I’m older than him,

but I got the smile from the pretty girl

and he just got pegged as a dick.

That’s what I call a successful trip

to the store.

Love of friends and family is transient, all the more precious because one day it will not be, as we will not be. “On finding Fernando Pessoa on a Sunny Day in May” celebrates the gift of friendship. The poet learns that his friend Fadil is about to publish a translation of poems by a poet with whom he is not familiar. So he finds the poet Pessoa’s poems and his delight is reflected in how he describes his patio and “the sun / still shining on my lawn. / Pessoa becomes / the big red umbrella / binding it all together.” Speaking of place, “Day by Day” is an “empty nest” poem, of “coffee cups and memories,” and grown children who have left home. The book’s title poem, “A Letter to Xhevdet Bajraj,” is poignant. It addresses the late brother of Jeff Weddle’s dear friend (and translator) Fadil Bajraj. “Fadil is amazing, and you / got to be his brother.” Weddle’s poem “When I’m Sixty-Four,” dedicated to his wife, Jill, is a declaration of love, passionate in its awareness that, ultimately, the world “will not “keep us.” The book concludes with a memory of the poet’s mother as a girl, who got to go from Kentucky to Chicago and meet a heartthrob of the time, singer Vic Damone. There’s a poem about the poet’s being at his father’s bedside in his final moments in a hospital, and a memory of being with his father in a barbershop, one of the strongest, most affectionate poems in this book, or in any book. His father eventually became “a professor of psychology. In “Haircut,” he says:

Buy I can remember him

cutting my hair,

shampooing it,

making horns on my head

with the suds.

I couldn’t have been more

than three or four

and my father was big and strong

and eternal.

And now, here we sit.

A tour de force of memory, well worthy of being anthologized, this love poem by a son about his father puts the reader “right there.”

Weddle’s talent for including the reader stems from reading other poets and from writing with no other voices in his head but his own. A seeker, he goes right to “what matters” and turns it into elegant language. In “RIP George,” a memory of his friend has moved him to say, “We were laughing inside five minutes / and that felt cheap, but it was real.” “Listen to Me Now,” about writing, is a metaphor for living. Listen to others, but then go ahead and do what you feel is right for you. He puts it bluntly. “Say whatever fucking thing / you actually mean to say.” Be your own person, in this complicated, tragic, beautiful world. In Letter to Xhevdet Bajraj, many truths lie beneath the surfaces of poems written because they had to be, and for the joy Jeff Weddle took in writing them.

About the Author

Peter Mladinic’s most recent book of poems, Maiden Rock, is available from UnCollected Press. An animal rights advocate, he lives in Hobbs, NM.

Peter Mladinic’s most recent book of poems, Maiden Rock, is available from UnCollected Press. An animal rights advocate, he lives in Hobbs, NM.