But in Bluff, Smith does something different that I find myself unsure of — they leave grandma’s kitchen and find a soapbox.

I fell in love with Smith’s work because of their confidence and authenticity; I would read their words and immediately felt like they were a second cousin from my momma’s side in the Midwest. And although this is not completely gone in Bluff, the overall composition of the book felt more like a collection on the Palestinian genocide and the perpetual endlessness of anti-Blackness, with whispers, hints, and sprinkles of personal truths. Danez Smith still has brief moments where they hop off the soap box, dap you up, bring you in, call you cousin, smell of pink lotion, and these moments are titled: “alive,” “Dede was the last person I came out to,” and, most importantly, “I miss that negro.”

But in the majority of Bluff, Smith’s ability to play with form gives their words a pulse, echo, and rhythm that brings the reader to a truth: people are dying and yet you are here, so what now?

Fearless in holding themselves accountable, Smith interrogates the possible performative nature of their own outrage, protest, and rebellion while also repetitively defining the current loss of humans and humanity. What is the true impact of marching for justice on behalf of the dead, only to return back home and breathe? And with that said, what of the silent or blind eye?

These poems are beautiful, pungent, thick, and difficult to swallow without water. And yet, the deeper I waded into the pages, the more I found myself, a Black woman in America, rolling my eyes back to the bottom of their sockets. I even wrote, “omg okay,” and “we get it,” and complained to a poet I love about this lackluster experience with the more politically direct poems.

I wrote, “I’m over the whole ‘a bullet is a gunshot is a son is crying in a mothers arm is a protest is a song is a cry is a bullet.’” And it is true. As a Black woman who is alive and loves poetics, I am very much exhausted by the redundant metaphor of being Black and fearful in America. I was disheartened that Danez Smith, who discussed the imperfect nature of loving those who hurt those who love you, was writing poem after poem about facts: genocide is bad, and racism is deadly.

And then I realized, those might only be facts to me. And Danez Smith. And people who see the world akin to me and Danez Smith. But millions of people see the facts of at least 45,805 Palestinians murdered by Israel in Gaza and respond with, “But I heard…”

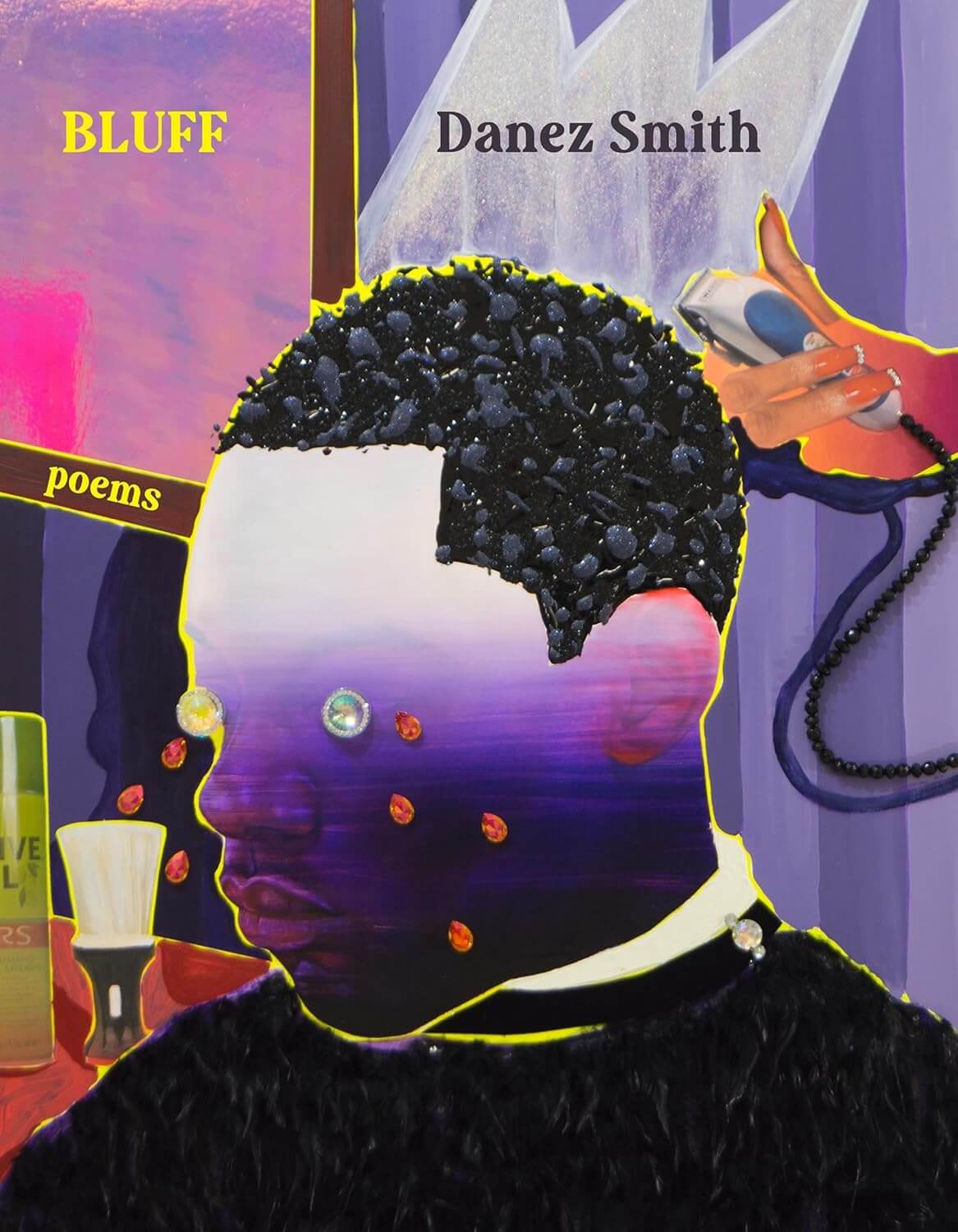

Danez Smith is devastatingly alluring, from the mustache to the earrings to the voice that listens and chides and loves. This is why Smith’s artistry can be found throughout Beyoncé and RuPaul’s internet, and even on Claudette Colvin and Pete Buttigeig’s public transportation. And with this grand opportunity for impact, Danez Smith has a chance to start amplifying the liberation.

Bluff was not written for me. It was written for those who are unaware of what it means to be Black in America or Palestinian in Gaza. What that fear does to the bones, or how it tastes on the tongue. It was written for those who have to realize the privilege of hashtagging about lives that will never go Instagram live again. Those who are being asked by Danez Smith to interrogate that privilege, do something with it, and make this space tolerable for those who suffer daily.

Innywho: I give Bluff 3.5 out of 5.

Pros: It is beautiful writing from a true wordsmith who is a master at familiarity, transparency, and emotion.

Cons: The soapbox moments withstanding, and this collection needs a trimming of the fat.

Favorite piece: “Two Deer in a Southside Cemetery.”

Stay connected with danez smith @danez_smif