Essay

On Translating Neruda

by Wally Swist

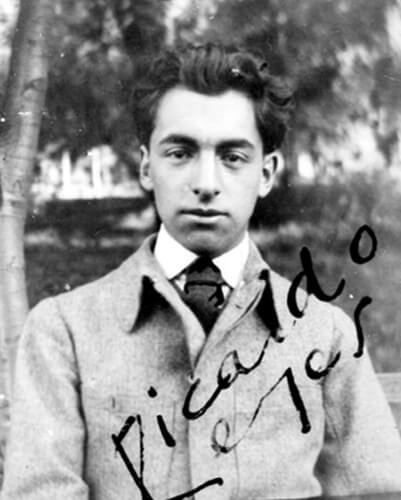

I had not thought I would translate my favorite poems of my favorite Spanish poets. I came to age in an era, as a bookseller, when translation was in what I have termed a golden age. W. S. Merwin’s translation of Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair was issued in the late sixties, and I memorized these poems by heart. There were many fine translators of Neruda, such as Donald D. Walsh, that I read early on, but I particularly admired and enjoyed the translations of Stephen Mitchell, whom I knew when he was a graduate student at Yale.

Robert Bly was an inspired translator and someone I found early direction from by reading his translations of Juan Ramon Jimenez and Federico Garcia Lorca in the early 1970s. However, I found Lorca earlier than that, as I recount in an essay I wrote regarding an early teacher of mine, for whom I had to memorize verses from Lorca’s “Romance Sonambulo.” The teacher’s name was Frank Aguilera, a graduate of Bowdoin College, who made a significant impression on me by his tone and style and certainly by his passion for Lorca.

If I took anything away from my Spanish studies, it was my love for Lorca. And it was a thoroughly different experience than that with my last Spanish instructor, a virago of a woman, who derailed my love of the language by her insensitivity and belligerence as a teacher that after taking that class with her, I lost interest in Spanish as a language and culture for several years. Although I can still claim that I once read Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote in the original Castilian, I can still hear her high heels echo imperiously past me when she walked the row of desks past mine.

My interest in poetry guided me to Lorca first by reading Alan Brilliant’s translations of some of the Andalusian songs he issued in a beautiful letterpress edition, Tree of Song, from his Unicorn Press in 1973. The selection has always sung to me; however, I did lose sight of the chapbook for some years, only to remember that I had given my copy away so many times that I needed to obtain another copy for myself—which I did. I propped the copy up near my writing table, and although I didn’t get to it for at least a year, when I eventually did, I heard the poems differently than in Brilliant’s translations and began to make my own translations. This then led to my rereading some of the work other translators had done, including and especially Bly, who, despite introducing so many worthy poets to so many readers, also takes, in my observation, such liberal interpretations of his own, which I believe do disservice to the poets he translates, especially Jimenez, whose purity of form, content, integrity of image, and his precision in what is elemental and sublime require a non-egoic interpretation.

My translating became not only a practice but an ardor, and I pursued it with zeal. After translating Lorca, whom I would return to again, I also returned to Jimenez after translating “Fruita,” which became not only a kind of beacon but a lighthouse—a lodestar shining many beacons. Along the way, I remembered the mystic St. John of the Cross, the superb imagist Antonio Machado, and one of my favorite poems from any language, “Canciones de cuna de la cebolla”/ “Bedtime Stories to the Onion,” a political poem with human overtones by Miguel de Hernandez. I will always be glad that Peter Thompson, editor of Ezra: An Online Journal of Translation, asked me if I had “any Miguel de Hernandez” after reading three of my translations of Neruda’s Odes in The Montreal Review. I said I did, sent him the poem, and Peter wrote back that it was “in the file” for a future issue of Ezra. Sometimes, alchemy actually does transpire.

What has happened to me, further and more deeply, is that I have come to appreciate the nuances in the authors I have translated. Jimenez’s sense of order in the disorder of the world is expressed by his predilection for the perfection of image, sound, and word. Lorca’s deep roots in the “guitar” and in Duende, the mysterious, dark creative force that predicates some, if not much, of Spanish poetry and song and his nearly inimitable penchant for fairy tales. If anything in Lorca’s work appears to be overlooked to me, it is his love of the mythological but especially of what is considered folk tale, fable, or romance. These worlds that open out for him and then for us are more real for him than what most of us consider life itself. Lorca lived his life within the bounds of the extraordinary, and we can see this opacity clearly in his work—and not just its magic but in its alchemical aspects that can transport us to realms that are more real and impossibly more beautiful. All of that is heard in his rhythms and his sense of song, rooted in the deep image.

Of course, there is Neruda, and the egalitarian stride of his poems, the international Whitman that emerges, the poet for every man and every woman. How could I pass up and not translate some of my favorite odes of his? With his breadth and depth, his sensibilities towards the sentience of life and the fullness of living, his odes, I believe, more than any of his other poems, leave their resonance in a reader’s mind. Like light shining up through the page, they not only charm us but leave us spellbound with a new sense of gratitude for what I call finding the numinous in the commonplace. To realize what is right in front of us all the time, and for us not to fully appreciate it, is just part of the gift of the legacy of Neruda’s odes, and among their nourishment we discover the astonishment of the awareness of living. It is my own intuition and belief that the three books of odes he composed in the 1950s were possibly one of the happiest periods of Neruda’s life.

May the translations I’ve made be as rewarding to any reader as they have been for me in making them. If you are aware of some of these poems in other translations, may mine be lanterns that might light up different corners of them for you to conceivably see and appreciate. If you are not aware of some of these poems, may they be felicitous first encounters, serendipities to be savored, as I still savor them. May the music and song in these poems leave you as enraptured, in many instances, as they have left and still leave me. May they reward you with the appreciation of what it means to be human and to be fully alive—in all senses and in every way you can possibly imagine.

3/Oda a la edad

Yo no creo en la edad.

Todos los viejos

Mediremos

Al hombre, a la mujer

mineral, un ave

Tiempo, metal

Ahora,

Ode to Age

I don’t believe in age.

All old people

Should we measure

To the man, to the woman

Time, metal

Now,

for the fish of the dawn!

About the Author

Wally Swist’s forthcoming books include and Aperture (Kelsay Books), poems regarding caregiving his wife’s struggles through Alzheimer’s, and If You’re the Dreamer, I’m the Dream: Selected Translations from Rilke’s Book of Hours (Finishing Line Press). Two collections of his translations from the Spanish are forthcoming from Pierian Springs Press: A Sense of Order in the Disorder of the World: Selected Spanish Translations and Untranslatable Song: The Vertical Poetry of Roberto Juarroz. Recent essays, poems, and translations have or will appear in Amethyst Review: New Writing Engaging with the Sacred, Chicago Quarterly Review, Commonweal, Deep Wild Journal, Full Bleed, Healing Muse, Illuminations, La Piccioletta Barca, Presence, and Your Impossible Voice. His book Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012) was selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the 2011 Crab Orchard Open Poetry Competition.

Wally Swist’s forthcoming books include and Aperture (Kelsay Books), poems regarding caregiving his wife’s struggles through Alzheimer’s, and If You’re the Dreamer, I’m the Dream: Selected Translations from Rilke’s Book of Hours (Finishing Line Press). Two collections of his translations from the Spanish are forthcoming from Pierian Springs Press: A Sense of Order in the Disorder of the World: Selected Spanish Translations and Untranslatable Song: The Vertical Poetry of Roberto Juarroz. Recent essays, poems, and translations have or will appear in Amethyst Review: New Writing Engaging with the Sacred, Chicago Quarterly Review, Commonweal, Deep Wild Journal, Full Bleed, Healing Muse, Illuminations, La Piccioletta Barca, Presence, and Your Impossible Voice. His book Huang Po and the Dimensions of Love (Southern Illinois University Press, 2012) was selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the 2011 Crab Orchard Open Poetry Competition.