Essay

Notes on a Poem: Nathan McClain’s Labor Day: Brighton Beach

by Robin Arble

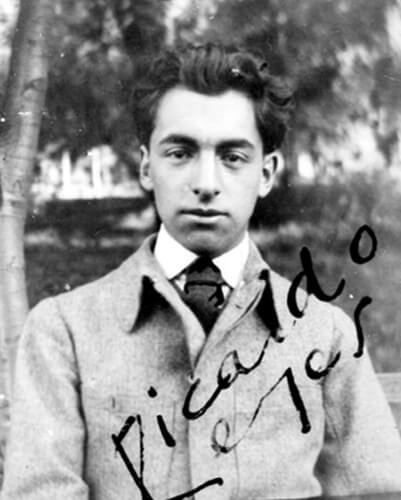

Nathan McClain is my poetry professor at Hampshire College, and he has always been a fanatical professor of craft, of form enacting content. He has also, at least since my first semester, been skeptical of the prose poem. So, it was a pleasure seeing not one but two prose poems in his new book, Previously Owned, as if he wrote both to challenge himself and knew he would succeed.

Nathan is skeptical of the prose poem because he thinks, like many, but not all poets, that the line break is a fundamental element of successful poetry, and any poem that abandons the line break must replace it with something that succeeds in doing everything the line break does. This is difficult but not impossible since Nathan succeeds in supplanting the functions of the line break in both of the prose poems in his new collection.

One of Nathan’s in-class maxims is “prose proceeds; verse reverses.” The line break—the eye darting back to the margin—turns the line into a unit of thought; a line break holds and withholds information and often manipulates this restraint and release with false or double meanings through the use of enjambment. If we consider the line break a grammatical function or even a form of punctuation—turning nouns into verbs, causing pauses—a prose poem can do all this without the visual rhythm of the line break.

Labor Day: Brighton Beach is one huge, pristinely grammatical sentence. It describes a long moment sitting in a lawn chair in the location in the poem’s title. The sprawling sentence enacts the panorama its language describes: a young woman “unfold[s] her nylon tent, smacking each stake into the sand with her sandal’s heel,” a plane “zip[s] past, tugging a banner for Wicked,” and “a jet ski, like a straight razor, slits the water’s surface.” The sentence’s length also suggests and enacts the length of the moment that is first and repeatedly described as “lovely” by a man who is “just a little tipsy.” If we consider the line a unit of thought, then this poem has no lines, or one long line, because the speaker has no thoughts, or one long thought, in his head.

A prose poem is often defined as a poem that contains all the usual functions of a poem except the line break. On the level of pure information, this is tautological, but it is useful reading and writing advice. Nathan’s poem contains imagery, musical language, and even a double theme. “Subject is pretext,” Nathan often says in class, meaning that a poem’s surface, sensory subject (“to have nothing to do but sit, shirtless, in my collapsible chair,”) inevitably leads to a discovered subject, something larger or intangible than its pretext (“to ignore beauty, or desire, or whatever,” “so I didn’t have to think about sorrow or loss, but let’s face it, I did,”). This poem acts like a poem, moves like a poem, and does everything line breaks do except break lines.

This poem replaces line breaks, then, with commas. Commas, in this poem, release and elaborate on information (“lovely to sit, beer in my lap”), reverse to refrains (“How lovely” “and lovely” “lovely, too”), and, with the help of dashes, obfuscate the meanings of certain phrases (“I didn’t have to think about sorrow or loss, though, let’s face it, I did, how not to—the old man missing a left leg—not how it happened, or when—but if it gets easier, you know, living with it,”). Grammar, punctuation, and syntax—imagery, music, and metaphor—have to work extra to make up for the absence of the line. Each of these elements hinges on the comma, the sense of “yes, and” that propels this sentence to its conclusion, “Carmen already asleep under a sun hat.” It is a pleasure, reading this poem, to watch Nathan—and his speaker—surprise himself.

About the Author

Robin Arble is a poet and writer from Western Massachusetts. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Oakland Arts Review, Beestung, Door Is A Jar, Pøst-, Brazos River Review, and Overheard Magazine, among others. They are a poetry reader for Beaver Magazine and the Massachusetts Review. She studies literature and creative writing at Hampshire College.

Robin Arble is a poet and writer from Western Massachusetts. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Oakland Arts Review, Beestung, Door Is A Jar, Pøst-, Brazos River Review, and Overheard Magazine, among others. They are a poetry reader for Beaver Magazine and the Massachusetts Review. She studies literature and creative writing at Hampshire College.