Review

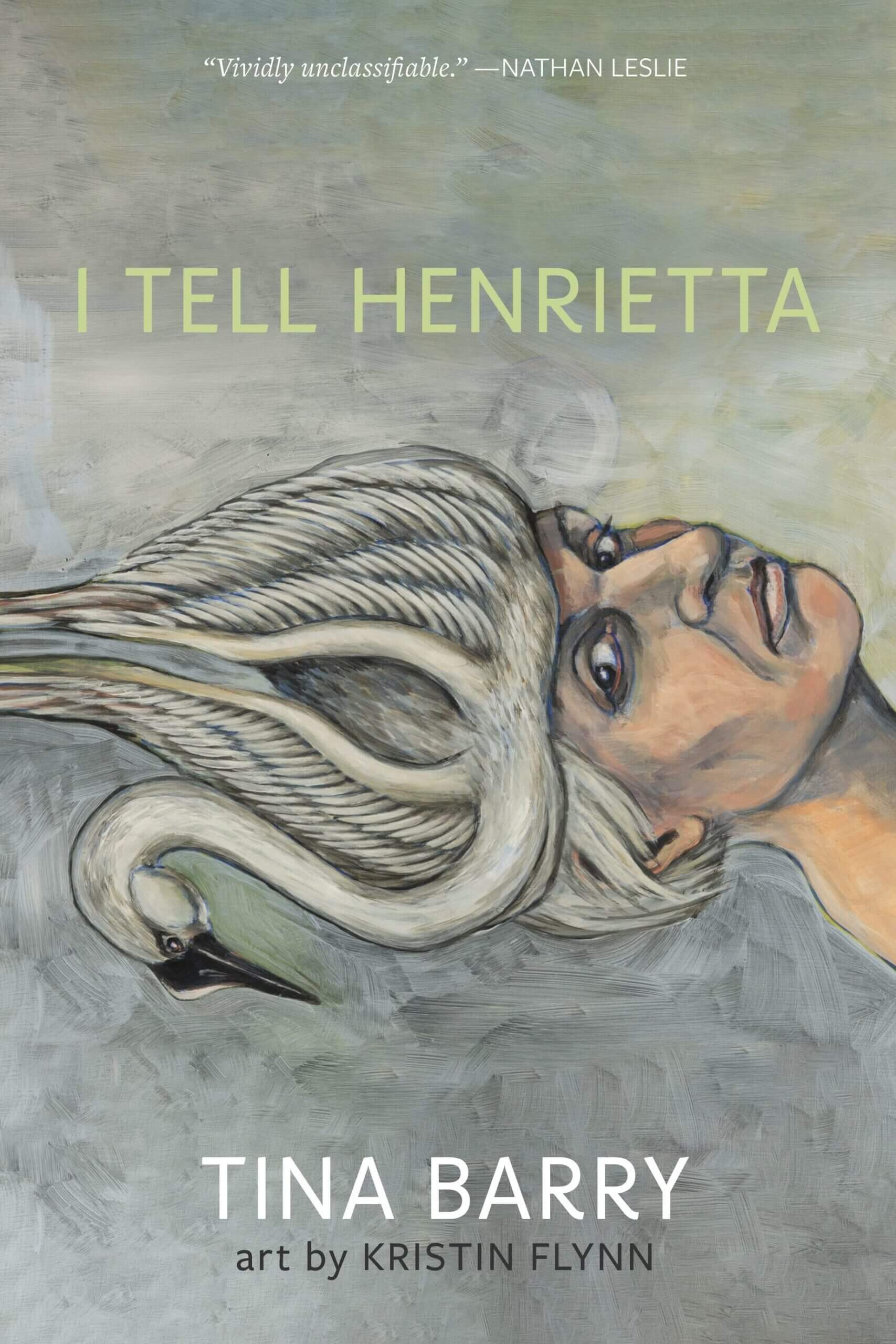

Berryman’s Henry, Barry’s Henrietta: A Review of I Tell Henrietta

By Tina Barry & art by Kristin Flynn

Aim Higher, Inc. ISBN: 979-8986369921

Review by Peter Mladinic

Two things to note about this book: it’s profoundly human and profoundly skillful. The poems are complemented by the fine illustrations of the artist Kristin Flynn. The beauty Barry renders in lines and rhythms, Flynn evokes in images and tones. I Tell Henrietta is about family, friends and acquaintances, and ultimately, the reader.

Barry’s Henrietta is the female counterpart to John Berryman’s Henry of The Dream Songs, though Henrietta is quieter, less visible, more subtle. As she appears in the title, she abides in this book.

The poems about family are accented by absence and presence: a father who leaves, a mother who stays, a sister, a husband, a daughter. In poem after poem, Barry writes about family with keen insight, showing and suggesting. “Arrival” is about an ultrasound. It begins:

“I tell Henrietta how I heard my mother’s heartbeat in her womb.” Here’s the second half of the poem:

… I hear my mother first, then feel the doctor’s wand

skidding through the puddle of gel on my belly … no sound, no

thud, the terror of that nothingness, until the doctor twists the dial

on the machine that brings my daughter’s life into the room, her first

insistent, pounding, I’m here.

It does injury to the poem to take these sentences out of context, but the continuity of grandmother, mother, and daughter, and the underlying “nothingness” and “here” attest to the beauty of mortality. The poet suggests we are here for a while and that we are cause for celebration. We are in that room with the doctor, patient, and the unborn.

Equally tactile, vivid, lucid are the poems about friends and acquaintances. “And Wonders About Old Lovers” begins, “I used to swim with the mother of an old lover.” The speaker, rejected by the lover, finds acceptance in the mother.

“My son is a fool for not loving you,” she said,

encircling me in her sea-chilled arms.”

It was the closest I’ve ever felt to anyone.

I kissed her shoulder.

In the poem that follows, “I Tell Henrietta About Rusty,” the tone is humorous. Rusty wanted his name tattooed above his girlfriend’s navel. She resisted this idea. “Fenders rusted after too many snowfalls. Cast-iron skillets, the kind I fried old Rusty’s eggs in, rusted.” A different man appears in “Zeus, Again.” “Something about the guy in the bar bothered me.” Yet, she accepted his invitation to a Halloween party. “On the night of the party, I opened the door to discover him dressed as an enormous swan.” What follows is exacting showing and telling, that caps off the humor. The humor, satires of suburbia, abides in “I Mention Our Neighbors’ Luau” and “Before Nanny Cams.” “Outliers” too has an element of humor, yet it’s also a comment on conformity.

In numerous poems about groups, the speaker is an observer. An example of Barry’s poetic insight comes through in “Outliers” as she comments on “hair teased high, busy with its own personality.”

Tina Barry never “gets caught writing poetry.” Her phrases are original, and alive. Writing about herself, she is inadvertently writing about her reader. Her swans symbolize beauty. To read “The Swan Returns, This Time With A Russian Accent” is to be in the hands of and hear the voice of a person very practiced in the art of the written and spoken word. “Before my daughter’s wedding, a swan slides/ through the dark folds of a lake.” She takes the reader from there through the humorous world of the poem:

I’ve accidentally given some thoughtless presents:

a wedge of cheddar to a lactose-intolerant colleague.

For a boyfriend, a birthday card addressed to my ex.

To a dying relative, a plant that attracted swarms of flies.

Flies in a poem about swans? She makes it work, marvelously well!

The swans also symbolize struggle, obsession, and joy. That’s clear in “My Year of Drawing Swans,” with its insightful phrasing: “Between its eyes, the black knob, gateway to the swoosh of neck,” and the tactile, “one arm around a subway pole,” which is brought back at the end of the poem. The conclusion’s ring of finality suggests things last for a while, we last for a while. Yet the accent is on “making.” As with the drawing of swans, so with the writing of the poems in this book.

About the Author

Peter Mladinic’s most recent book of poems, House Sitting, is available from Anxiety Press. An animal rights advocate, he lives in Hobbs, New Mexico, United States.

Peter Mladinic’s most recent book of poems, House Sitting, is available from Anxiety Press. An animal rights advocate, he lives in Hobbs, New Mexico, United States.