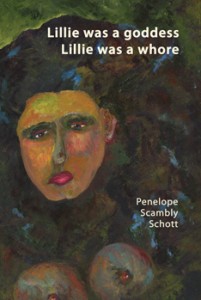

Penelope Scambly Schott’s sixth full-length poetry collection, Lillie was a goddess, Lillie was a whore, examines prostitution throughout history. The title character appears in different manifestations throughout the book and is named after the mythical Lilith, Adam’s first wife who was exiled from the Garden of Eden for insisting that she be on top during sex. Lilith is associated with prostitutes because of her sexual transgressiveness, but while this rebelliousness results in marginalization, it also offers a certain power. As “Why a Happily Married Man Would Go to a Prostitute” asserts, “after one night with a daughter of Lilith, no man / can be satisfied with a mortal woman” (17). Lilith has been reclaimed by many feminists as a role model, which is true of Schott’s Lillie. While she is oppressed by patriarchy, she remains defiant, refusing to lose her selfhood and working the system to her advantage.

The book consists of sixty poems divided into three nearly-equal sections. The first section, “Prostitutes in the History of the World,” examines prostitution as an economic exploitation of women. It is the collection’s angriest section. Six of the twenty-one poems are written from men’s perspective in order to establish their role as oppressors. Two of the section’s best poems are the deliciously-cutting and sarcastically-titled “He Nicknames What He Loves and Takes It Out to Dance” and “Thumb-Indexed Alphabetized Blue Book for the Sporting Man-about-Town,” both of which are list poems for names of penises and brothels, respectively, and show how society’s obsession with sex often leads to objectification.

In the second section, “Lillie in the American Wild West,” Lillie solidifies as a character, describing her adventures servicing men in nineteenth-century California and Oregon. She is stronger and more independent in these poems, becoming a shrewd business woman and enjoying the opportunity to learn about the world via her travels. While the job is drudgery and, as in “Lillie Used to Eat Oatmeal with Fresh Cream,” she looks forward to the end of each workday when “I can unstring my bodice and wash / off everything sticky” (39), she also sees the value in her work. The final lines of the section’s last poem, “Miss Lillie Finally Retires Back in Portland,” are “I think of those fellows, hundreds / or thousands of men, how grateful / they were, how many lives I saved” (55, italics in the original). Her companionship is just as valuable as her sexual services and something human enters the impersonal business transactions.

The final section, “Nothing New Under the Sun,” examines prostitution in the digital age. Most notably, there are list poems of online sexual services ads; “Tick-Tock, Time to Fuck”, “The Classifieds Celebrate Our Saviour’s Birth, Alleluia”, and “craigslist” show that economic inequality is just as much a part of sex work now as it has ever been. Like Lillie in the second section, the women in the book’s final third learn to squeeze as much advantage as possible out of their difficult situations. “Lilah’s Learning Curve” ends “you wise up / and fire the pimp boyfriend / and double your price” (61). This feistiness epitomizes Lillie was a goddess, Lillie was a whore’s unbowed tone.

Nineteen of the poems, scattered randomly throughout the collection, are followed by tercets told from the perspective of Lillie’s customers. The following is representative of these:

Lillie was her knockers, Lillie was her snatch.

When I knocked at Lillie’s house,

she lifted up the latch. (17, italics in the original)

These nursery-rhymish mini-poems portray Lillie as an object and her customers as oafs, thus enhancing the power of the longer poems told from her perspective which focus on her entire being.

There is also a series of seven versions of “Why Lillie Became a Prostitute.” These poems tie the book’s three sections together despite their different foci. We are given reasons for Lillie’s decision, such as experiencing sexual abuse, economic hardship, seductions gone wrong, the desire to see the world, and the desire for material things. The final version begins “Whatever I tell you, you won’t believe me.” Despite the hopelessness of this statement, the poem ends with “I really love sex and can’t get enough” (78). The ambiguity of this line—is Lillie sincere, or is she laughing at us, simply repeating what her customers and we as readers would like to hear?—works as a reclaiming of power that has been stolen from the speaker by society’s judgment that she only has physical worth.

Lillie was a goddess, Lillie was a whore is well-researched, as the sizeable bibliography attests. Aside from a variety of academic histories of prostitution and a few volumes on the history of female deities, the list includes several personal interviews (presumably of sex workers) conducted by Schott. This devotion to her subject matter is admirable and portrays a strong statement that poetry can be art without being disconnected from the fight against oppression.

As with any poetry collection, the quality of poems is uneven. Some slip over the line into preachiness, but most are well-crafted and engaging. Lillie was a goddess, Lillie was a whore coheres well and is an enjoyable, worthwhile read.

Lillie was a goddess, Lillie was a whore

By Penelope Scambly Schott

Mayapple Press 2013

ISBN: 978-1936419258