Letter from Hong Kong

By Lucas Klein

Reviewing exiled Chinese poet Bei Dao’s first full-length collection The August Sleepwalker in English in 1990, a professor quipped, “These could just as easily be translations from a Slovak or an Estonian or a Philippine poet. It could even be a kind of American poetry….”

From a certain perspective—say, that of the seventeenth century—the reviewer was right. The defining characteristics and qualities of Biag ni Lam-ang, a Filipino epic transcribed around 1640, would have been very different from that written by Vavrinec Benedikt z Nedožier (1555-1615), though his verses may have shared features with Estonian poetry as inaugurated by Reiner Brockmann in 1637. Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672), too, would have been noticeably different. And all these should have been immediately distinguishable from seventeenth-century Chinese poetry, such as by Wu Weiye 吳偉業 (1609-1671), famous for his narrative poems but also able to write intricate metaphors of precise detail, as in “Ancient Feeling” (translated by Jonathan Chaves):

Beloved, you are like the thread in the loom

woven into a flowering tree of love!

I am like the flowers on your robe:

the spring wind blows but they won’t drop off.

From such a point of view, most poetry from around the world today must look very similar, indeed, having been bred from cross-pollination and intercultural miscegenation. But from the perspective of poetry today, which is to say, from the perspective of people who habitually, consciously, and conscientiously read contemporary poetry around the world, do all cultures and languages and poetries blend together?

The International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong 香港國際詩歌之夜, which has been taking place biannually since 2009, offers one place to test the question, as invited poets have included poets from Eastern Europe, the Philippines, the Americas, the Chinese-speaking world, and many other regions of the globe. The festival is organized by Bei Dao 北島, born and raised in Beijing but living in Hong Kong since 2007. Exiled from mainland China in 1989 after a poem he wrote in the seventies was recited at the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, he lived in several countries in Europe before settling in the US in 1993. Only after a stroke in 2012, with the chairwoman of the Chinese Writers’ Association personally vouching that he would avoid both political and literary activities, has he been allowed a multi-entry visa to the PRC for medical treatment.

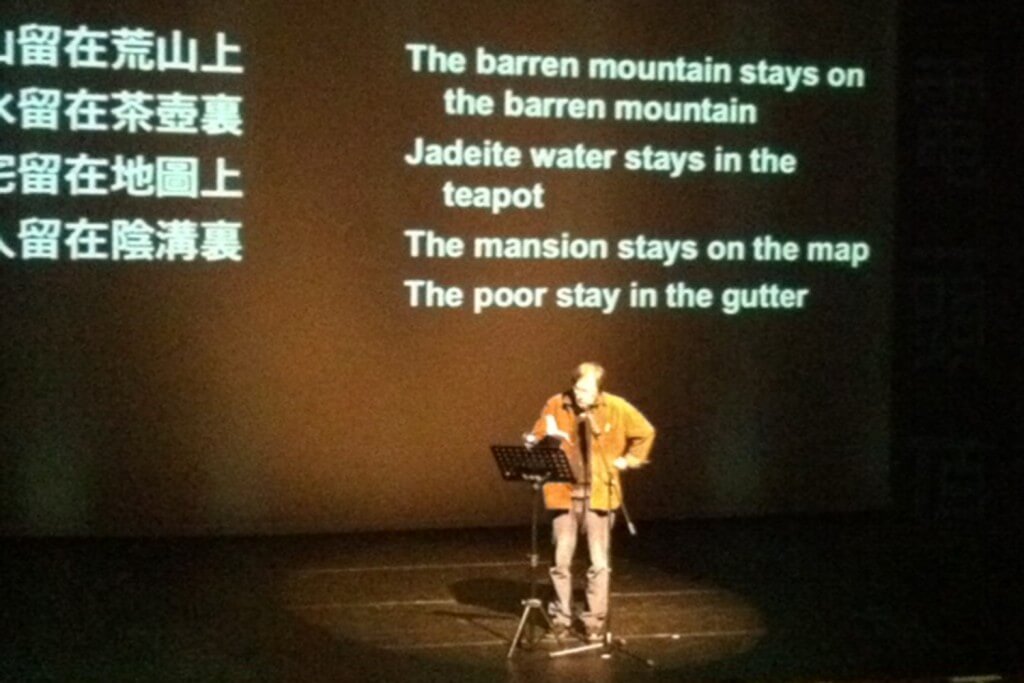

Photo of Xi Chuan reading at International Poetry Nights by Lucas Klein.

A clear motivation for the International Poetry Nights is to combat Hong Kong’s reputation as a cultural wasteland. Whereas Bei Dao started writing poetry against the overly politicized language of the Cultural Revolution, today he frames his poetry in opposition to linguistic commercialization.

“We live amidst separate jargons,” he wrote in the introduction of the 2011 Poetry Nights, “scholarly jargon, businessmen’s jargon, political jargon, and more…and in the internet age of so-called globalization, vulgar and elegant meld to form a common pact, simplifying humanity’s linguistic expressivity.”

Multilingual anthologies comprising poems of the international participants, The Other Voice 另一種聲音 (2009), Words and the World 詞與世界 (2011), and Islands or Continents 島嶼或大陸 (2013), are available from Chinese University Press or its international distributor, Columbia University Press. From 2011 on, the anthologies can come as part of boxed sets featuring individual pocket-sized volumes by each participating poet. (See this review of the Words and the World set at Rain Taxi.) All poems are translated into English and/or Chinese and printed with their original languages. Since the 2011 Poetry Nights, I’ve served as translation editor for the books and festival.

* * *

We have not had Slovak or Estonian poets, but Albanian poet Luljeta Lleshanaku, from the 2009 festival, and Russian Arkadii Dragomoshchenko and Slovene Tomaž Šalamun, from 2011, may serve as sufficient examples, as will 2013 Filipina participant Conchitina Cruz and American Jeffrey Yang. From Lleshanaku’s “Marked” (translated by Henry Israeli and Shresa Qatipi):

My deskmate in elementary school

had blue nails, blue lips, and a big irreparable hole in his heart.

He was marked by death. He was invisible.

He used to sit on a stone

guarding our coats

as we played in the playground, that alchemy of sweat and dust.

The “deskmate” suggests the classroom organization common to schools in state socialism, but Dragomoshchenko, who would have had a similar schooling, writes differently. From “Elegy on Rising Dust” (translated by Lyn Hejinian):

Spring’s scales are shadowless like the brain’s axe-head

And blood is revealed in concealed transformations

As if it were a substance rising to the zenith

Then falling back to the nadir of pure speech

That leads off endlessly to dreams of birth

And contemplates itself in the husk around essential matter.

Like so: in the gliding of the swift

In the instant the lizard darts from the shade—

The foregrounding of linguistics resonates with contemporary American Language poetry, befitting translation by Hejinian, but Šalamun (b. 1941) represents a different engagement with contemporary America. “Folk Song” (translated by Charles Simic):

Every true poet is a monster.

He destroys people and their speech.

His singing elevates a technique that wipes out

the earth so we are not eaten by worms.

The drunk sells his coat.

The thief sells his mother.

Only the poet sells his soul to separate it

from the body that he loves.

Again, an interrogation of poetry, but with a sense of substance, however frightening, beneath the rhetoric. Meanwhile, Cruz, who writes in English, writes about global circulation, as in “Here”:

In Manila, I spend an inordinate amount of time around copy machines.

In the cheap hotel, I peel an apple with a Swiss knife.

In my childhood bedroom, I weep over an unpresentable pincushion made for sewing class.

In Bali, I am too embarrassed to say no to a manicure.

In Makati, I take off my heels and slip into flats.

In the coffee shop, I write the incriminating postcard.

In the ballet studio, I am amused by my catastrophic pirouettes.

In Chicago, I attempt to mimic an old roommate’s unidentifiable accent.

In Bangkok, I am addressed in Chinese.

Where Cruz may be addressed in Chinese, Jeffrey Yang’s poems are often addressed to Chinese, though also about global circulation. “Xiangjun”:

Follow the twelfth guideway thru

the Middle Mountains to the realm

of the Nine Rivers where Xiao

flows into Xiang and tear-stained

bamboo grows. In this place four

thousand years ago the Xiangjun

drowned themselves: two daughters

of Yao, wives of Shun. Not even

geese can bear their water-spirit

sorrow. Tang Poet Qian Qi:

Why rashly turn back once at the Xiao-Xiang

Blue-green waters bright sand moss on both banks

Twenty-five strings plucked on moonlit nights an

unbearable pure melancholy so they take flight

Including Chinese legend and his idiosyncratic translation of Qian Qi 錢起 (710 – 782) puts Yang in more conspicuous dialogue with Chinese tradition than many poets writing in Chinese.

As for Chinese poetry, it does not necessarily sound like itself, though I do not think that makes it less Chinese. Bei Dao is not Eastern European, even when he writes in dedication to Chuvash/Russian poet Gennady Aygi, from “Tribute” (translated by Eliot Weinberger):

a storm screams in a kettle—

the homeland is leaving from the platform

open your window

this moment leads the days of the past

like wild geese heading south

But neither does he sound like Xi Chuan 西川, as in “A Sanskrit Brick from the Nanzhao Kingdom (738–937 ce): after a Vietnamese poet” (translation mine):

An antique shop on Jadestream Road in Dali’s old quarter. A gray-green brick in the shop from the late Nanzhao era. On the gray-green brick eleven lines of Sanskrit. The hands that molded the Sanskrit lines. The hands that inlaid the brick into the base of the pagoda. The late Nanzhao monk who could read the eleven lines of Sanskrit. The man or men who brought Sanskrit from India through Nepal to Nanzhao. Buddhists. Buddhists who had or had not achieved nirvana before dying, and the loiterers who couldn’t give a damn about achieving nirvana. Problems Hīnayāna Buddhism encountered never encountered by Mahāyāna Buddhism. The pain the emperor of Nanzhao suffered unbeknownst to the emperor of Tang. The dusk of Nanzhao kingdom’s demise. The thugs who knocked over the pagoda. The astonished onlookers. 902 CE. From then till now, countless I’s have searched for this gray-green brick molded with eleven Sanskrit lines. In this antique shop on Jadestream Road in Dali’s old quarter, coming down with a cold and with a runny nose, I pulled the gray-green brick out of the glass case, held it in my hands, and in the end talked the clerk down from 800 to 430 RMB. Just by shifting my hand, I could have dropped it and watched it shatter. But the notion passed in an instant. Also present were the poet Song Lin and a spider dangling from the rafters.

And yet both these poems strike me as indelibly Chinese.

Of course, that is a Chinese very different from the Chinese found in Taiwanese poetry—such as Ye Mimi’s “A Moth Laid Its Eggs in my Armpit, and Then It Died” (translated by Steven Bradbury):

One day there’ll come a day / when the rain will not be wet / the avenue uneven / the grass undry umbrellas

unbroken / the sky bent out of shape / a day when sand and surf have gone their separate ways

/ the breeze unveiled its fine-tooth milk-teeth / and clouds have it all over fog for puttin’ on a happy face

then everyone will / move into their very own phone booth / keep a puppy at the welcome mat /

/ or a peacock / or a cat

—or Hong Kong poetry—like Natalia Chan’s “The Loving Wind and SARS” (translated by Eleanor Goodman):

From now on we keep three feet apart

from now on I wear a surgical mask to talk with you

from now on we can’t hold hands, just say goodbye

until my body’s severe, acute love for you

produces antibodies

—as these poetries reflect the different directions Chinese culture has taken in its interactions with the rest of the world.

* * *

While the poems I’ve cited here don’t sound like poetry in any language from four centuries ago, I do not think they sound indistinguishable from each other. Rather, they sound like languages in dialogue, as Bei Dao’s dedication to Aygi and Xi Chuan’s inspiration from a Vietnamese poet attest.

Within this dialogue, cultural rhythms still ring through. Writing to Dragomoshchenko in “Untitled” (translated by Odile Cisneros), Régis Bonvicino describes Brazil:

the sun shining through the trees

on a clear autumn day

Brazil is a jungle where snakes

devour cake on the streets

And I can hear a Hispanic passion even in English in Maria Baranda’s “Letters to Robinson” (translated by Joshua Edwards):

Listen, listen to time’s detonations.

Don’t confuse the aviator’s signs

with explosions formed on the tongue.

Powerful provocations. Time of scales.

Filth from the skin and its stubble.

Jacob Edmond has shown that Bonnie McDougall’s translation of Bei Dao’s early work targeted a universalist aesthetic, showing at once the validity and fallacy (depending on emphasis) of the review I quoted in the first paragraph. But if so much depends on the translation and the translator, how do these poems sound when translated into English and Chinese?

A particular test case is Swedish poet Aase Berg. She invents words, and her translator, Johannes Göransson, matches her coinages with made-up words in English. When Göransson found out that Berg was going to be translated into Chinese, he posted on Facebook, “I would love to be able to read those translations. I mean, you might think my translations of all those neologism etc into english are weird. What are they doing in chinese? The more ‘impossible’ the translation, the more interesting it is to me.”

Someone replied, “Weirdly, the word combinations in Chinese might be more natural than in English or Swedish, since Chinese is written with no breaks on the page, and words are more explicitly formed as combinations of symbols.”

Here is one of Berg’s poems, with Göransson’s translation, “Ouroboros”:

värka ut ur tuggomväcka tidens tandvinka klumpt koralliskhuggorms kladdinghand

äggu! hättä!, äspinggapet av en gaspinggaddvampyrets giftstingbiter på ingenting

lindorm ömsar summanav en bitring

ache out of chewupwake time’s toothwave clumped corallicstingviper muckhand

äggu! hättä!, viperthe gape of a yawningvampirebiter’s poison stinghas no bite

swaddle snake sloughs off sumof a teething ring

To compare this with the Chinese version, by Chen Maiping 陳邁平 (penname Wan Zhi 萬之), writer and co-founder with Bei Dao of the re-born literary journal Jintian (Today) 今天 in exile in 1990 (and husband of Anna Gustafsson Chen, Swedish translator of Nobel literature laureate Mo Yan 莫言), takes some work. When she spoke at the “Poetry & Globalization: Opponents or Partners?” panel during the Poetry Nights in Hong Kong, Berg said that she did not want her translator to be “faithful,” but rather to put forth his own creative interpretation of what she was doing in her poetry in Swedish.

Based on what Göransson has written, in his note to his translation of Berg’s Transfer Fat (Ugly Duckling, 2012), for instance, he is absolutely on her wavelength. My own tendency in translating is the opposite: I want my translation not to be an expression of myself, but rather an expression of someone else. Though of course I cannot but present my own interpretation, even so.

Here, then, is Chen’s translation of Berg’s poem, “銜尾蛇”:

疼痛出自嚼顎

喚醒時代的牙齒

招手不雅是珊瑚的

蝮蛇的塗髒手

哦唔!喵唔!雌蝮蛇

一個哈欠張大嘴吐舌

蟄刺吸血鬼的毒蟄

刺咬在無有一個

林德蟲蛻皮替換

一個咬環的全部

Chen provides extensive annotations to his translations. He explains that “Ouroboros” is a snake eating its own tail, and notes the alliteration and consonance of Berg’s Swedish. He explains that a lindworm (Ch. linde chong 林德蟲; Sw. lindorm; what for Göransson is “swaddle snake”) is a flying dragon, wingless and legless, from Norse legend, as well as the namesake of a noted Swedish poet. Literary translators in English often reject footnotes as features that intellectualize and therefore break the reader’s emotional connection to the literary product. Translators in Chinese, with a longer tradition of annotation and a different relationship to reading global masterpieces for pleasure or edification, do not necessarily see it that way. Chen notes that Berg wrote many of these poems of mythological creatures for her then newborn baby, hence onomatopoeiae such as äggu! hättä! (I think this explains Göransson’s “swaddle snake”).

To translate this properly, I should also look into how Chinese translators have handled other poets who employ neologisms. Paul Celan, for instance, has been translated by Wang Jiaxin 王家新 (I believe from intermediary English versions, though I don’t know whose; translating from Michael Hamburger’s Celan would be very different from translating from Pierre Joris’s). How has Celan’s translator handled the new coinages, and has that handling informed Chen’s handling of Aase Berg’s Swedish? (Many have noted that Celan’s de- and re-composition of post-Shoah German is matched by what Bei Dao and his generation of poets have done with post-Cultural Revolution Chinese.) In his notes, though, Chen only mentions one coinage, jiao’e 嚼顎, to match Berg’s tuggom, from tugga and gom.

I should also try not to be influenced by Göransson’s version, or rely on his terminology to find English equivalents to Chen’s Chinese equivalents to Berg’s Swedish. To echo Göransson would weight the translation so much that my English version could not be put beside it (even if, though I don’t know if this is the case, Chen Maiping consulted the available English translations before finishing his Chinese versions).

pain comes from chewjaw

teeth in the time of being woken

wave hands inelegant are coral

pit viper’s scrawl-dirty hands

o wu! miao wu! mother pit viper

a yawn opening mouth wide tongue out

stinger vampire venom

stinging in nothing

lindworm sheds skin to replace

a teething ring’s totality

Walter Benjamin said translations were themselves untranslatable because in them meaning adheres to language too loosely, too fleetingly. His view of language makes no sense, but translating translations is hard, nonetheless.

In my version, questions remain. Göransson’s friend’s post that in Chinese “words are more explicitly formed as combinations of symbols” is a fantasy. (More likely, because there are no spaces between words and such a range of combinatorial possibilities, there’s less conventional freedom to coin your own words.) But it is indeed hard to decide what is attributive or predicative—or even noun or verb—in what I have translated as “wave hands inelegant are coral / pit viper’s scrawl-dirty hands,” or for that matter if “coral” describes the hands, the inelegance, the pit viper, or its “scrawl-dirty hands” (whatever they might be). In other words, the Chinese offers no certainty from which to judge if my translation is right or wrong, or if it is anything but my own limited understanding. Even when translating from Chinese, the translator can only translate as Berg wishes, which is not to be limited by Berg’s own designs on the poem.

* * *

In the aforementioned “Poetry & Globalization” panel, Ye Mimi said that poetry for her was wholly individual, and therefore unrelated to globalization. (The other panelists, including Aase Berg and Jeffrey Yang, disagreed.) Looking at the cross-cultural similarities and differences of the Poetry Nights poems I’ve quoted, and of what happens in translation from Swedish to Chinese to English, I also have to disagree. (As an aside, Johannes Göransson wrote about Aase Berg’s enthusiasm for Ye Mimi’s poetry, her comparison of it with Tomas Tranströmer, and what it has to do with our understanding of translation).

Poetry, or one’s response to it, is certainly individual, but it also takes part in an international, translingual, and cross-cultural conversation. And while this conversation creates similarities and resonances, because each participant is bound by its own position within its language and culture, differences and misprisions and distinctions emerge. Local culture, in other words, is not going away because poetries are in dialogue with each other around the world.

In that respect, poetry today at once owes its existence to a certain kind of globalization, but at the same time can combat the sort of globalization in which all of us, around the world, end up learning the same language, eating the same foods, and wearing the same clothes. Poetry, that is, presents a vision for an alternate globalization. It allows us to ask if poetry from China and Slovakia and Estonia and the Philippines and any part of the Americas is the same, and to answer that question in the negative.

Islands or Continents: International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong (also as 18-volume box set)

Edited by Gilbert Fong, Shelby Chan, Lucas Klein, Bei Dao, and Christopher Mattison

The Chinese University Press (March 2014)

ISBN: 9789629966041

ISBN: 9789629966058 (box set)

Words and the World: International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong (also as 20-volume box set)

Edited by Gilbert Fong, Shelby Chan, Lucas Klein, and Bei Dao

The Chinese University Press (April 2012)

ISBN: 9789629964955

ISBN: 9789629965129 (box set)

The Other Voice: International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong

Edited by Gilbert Fong, Shelby Chan, and Bei Dao

The Chinese University Press (September 2010)

ISBN: 9789629964405

About the Author

Lucas Klein—a former radio DJ and union organizer—is a writer, translator, and editor whose work has appeared in Jacket, Rain Taxi, CLEAR, and PMLA, as well as from Fordham, Black Widow, and New Directions presses. Assistant Professor in the School of Chinese at the University of Hong Kong, he is the translator of Notes on the Mosquito: Selected Poems of Xi Chuan 西川, which won the 2013 Lucien Stryk Prize for Asian poetry in translation and was shortlisted for the Best Translated Book Award in poetry (see http://xichuanpoetry.com). He is at work translating Tang dynasty poet Li Shangyin 李商隱 and seminal contemporary poet Mang Ke 芒克.

Lucas Klein—a former radio DJ and union organizer—is a writer, translator, and editor whose work has appeared in Jacket, Rain Taxi, CLEAR, and PMLA, as well as from Fordham, Black Widow, and New Directions presses. Assistant Professor in the School of Chinese at the University of Hong Kong, he is the translator of Notes on the Mosquito: Selected Poems of Xi Chuan 西川, which won the 2013 Lucien Stryk Prize for Asian poetry in translation and was shortlisted for the Best Translated Book Award in poetry (see http://xichuanpoetry.com). He is at work translating Tang dynasty poet Li Shangyin 李商隱 and seminal contemporary poet Mang Ke 芒克.